For decades thousands of unmarried pregnant Australian women were pushed into a world of shame, forced to have their babies in secret then give them up for adoption, as Nick Toscano reports.

JAN Russ kept reaching for more soap. Head to toe, scrubbing, scouring and rinsing beneath the shower’s sharp spray, unable to stop. It was like she was under a spell.

But on this day, after she’d flown back from Canberra, her behaviour wasn’t so bizarre. She was finally able to wash away the sense of unworthiness, the lifetime of shame, the feelings of being a ‘‘slut’’ and a ‘‘naughty girl’’ — feelings that had weighed her down since she fell pregnant as a teenager some five decades ago.

‘‘You were told, ‘If you love your baby you should give it up, because you can’t give it a normal home’,’’ Jan recalls. ‘‘You were just pushed down all the time, made to feel worthless, told you weren’t good enough to look after your child.

‘‘It was brainwashing coercion.’’

On February 29, Parliament House roared with applause as senators rose from their red leather seats to acknowledge the dozens of women watching from the gallery.

Jan clapped back at them, her eyes welling with tears. Her story, like those of the other women who made the trip to Canberra, had at last been heard. What they’d endured had finally been deemed ‘‘criminal’’.

After 18 months of taking evidence, Senators handed down a report recommending a national apology to thousands of mothers.

It’s estimated more than 150,000 babies were put up for adoption in Australia between the 1950s and ’80s, but for many mothers it wasn’t a choice freely made.

The practice, known more recently as forced or coercive adoption, was common, as authorities failed to gain free and informed consent from scores of young, unwed mothers before their newborns were removed.

Many unmarried mothers automatically had their hospital records marked for adoption, and were not told of their rights or of the 30-day cooling-off period to opt out. Instead, they were often drugged with sedatives, pressured into signing papers and shackled to their beds while giving birth before their babies were whisked out of sight.

Jan’s arms were tied down and her legs strapped in stirrups when she was in labour at Sydney’s Mater Hospital.

It was the 1960s and pregnant, unwed women Australia-wide were shunted into a world of shame, either hidden at home, or packed off interstate to special homes for unmarried mothers-to-be.

For Jan, as a terrified teenager, the price of acceptability was isolation. All alone, she left her family home in leafy Maribyrnong and made the trip to Sydney to have her baby in secrecy. In a brick-walled back room of the hospital, fitted with World War II-era iron beds, she was kept separate from the married mothers of the maternity ward and treated with disdain.

‘‘A sister came into me and said, ‘Shut up, shut up! You are making so much noise … don’t you realise there’s a married woman trying to have her baby down the hall, and you’re upsetting her’?’’

The next thing she remembers, the nurse told the doctor Jan was tearing. ‘‘ ‘Oh, don’t worry about her, just let her rip’, the doctor said – it’s as clear in my memory today, and then my baby was born. All I could see was this little thing covered in blood and muck.

‘‘I yelled out, ‘What’s my baby, what’s my baby? Is it a boy or a girl?’ They said it was a girl and took her away.”

Jan was afforded no support and instructed to forget the whole experience, a practice that’s resulted in a lifetime of grief, shame and anger for many women.

Coleen Clare, manager of Melbourne-based adoption search and support group Vanish, says many girls who had relinquished their children now realised the wrongs they’d faced.

‘‘They certainly weren’t told there was any sort of housing, support or income they could apply for,’’ she says. ‘‘They weren’t given a reasonable deal.

‘‘That’s how we define being forced — people giving consent well under the age of 18, being given drugs to dry up their milk, but which were also very sedative, having nobody there to support them or speak to them, and they were isolated and shamed while they were in hospital.’’

Adoption had been regarded as the solution to the dual issues of infertility in married couples and the shame of giving birth out of wedlock. It was considered at the time to be in the best interests of mothers and babies alike. But the stories that have emerged showed there were serious repercussions for mums, dads and the children they were separated from.

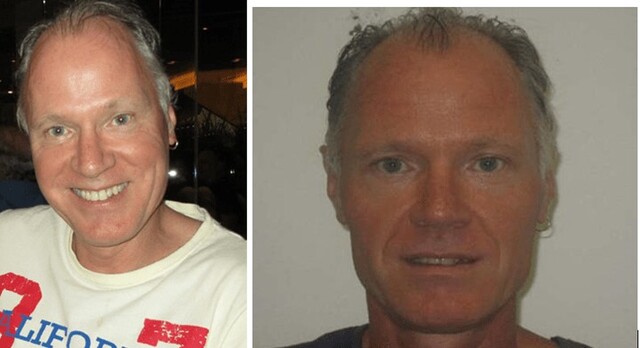

Gary Coles wasn’t present when his son was born in New Zealand, which also practiced forced adoption, in May 1967. When he and his girlfriend, Kay were students in their early 20s, ‘‘one night of passion’’ led to an unexpected pregnancy.

‘‘From the moment Kay told me the news, the damning phrases ‘illegitimate’ and ‘conceived out of wedlock’ began to resonate.’’

With no financial or moral support from his disapproving father and having to hide the pregnancy from Kay’s staunchly Catholic family, fright became flight, and Gary left Kay.

Their son, ‘‘Mark’’, spent 11 days in a hospital nursery before being adopted.

But in a letter, Kay later told Gary that being spared the wrath and disappointment of her parents couldn’t compensate for the profound sorrow she felt when her son was taken from her.

To this day Gary, who now lives in Bacchus Marsh, is unsure whether Kay would’ve chosen to keep their son if she had been able to hold him, bond with him, and if she had been told of the legal opt-out period after signing the adoption papers.

Two decades later, Gary decided to reach out.

Among his first steps was adding his name to his son’s birth certificate, which New Zealand law permitted with Kay’s consent.

‘‘From the adopted person’s point of view, having the father on the birth certificate means it won’t just be assumed that the mother didn’t know the father,’’ Gary says. ‘‘I’m an example of a father who does care, and I couldn’t reach out to my son without officially being recognised as his birth father.’’

A coffee catch-up in 2009, his first meeting with his son, showed a relationship may prove difficult to cement. Now married with two children and working as a lawyer, Mark sat tight-lipped and indicated he preferred the status quo. Gary has since reduced his contact to yearly birthday cards, but still hangs onto hope.

Kyneton resident Maggie Millar has experienced the pains of Australia’s past adoption practices from both sides. First, by living what some refer to as the ‘‘shadow life’’ as an adoptee, and later, as a woman who has carried the loss after financial pressure forced her to give her own child for ‘‘closed’’ adoption.

Maggie recalls growing up with a love for art, piano, music and ballet, but ‘‘no one else in the family had any of that’’.

When she was 17 she learned the truth during a heated argument with her adoptive mother. “You’re not your father’s daughter!”

While she recalls it was a shock, it came as no surprise. It explained why she never felt at home with her relatives, but sparked many questions she couldn’t yet answer: Who am I really? Where’s my real mother? Do I have any sisters or brothers?

After Maggie met her birth mother years later, she was launched on an incredible journey of self-discovery, still finding things out today ‘‘at the ripe old age of 71’’.

‘‘My mother was addicted to cumquat marmalade, I’m addicted to cumquat marmalade … she even runs her fingers across the plate, the same way I do,’’ Maggie laughs. ‘‘These things are important, they give you a sense of place in the world.’’

Maggie learned her mother wanted to keep her, but after her family sent her to a church-run home to hide her pregnancy, she was made to feel a sinner.

Maggie knew exactly what her mother had gone through.

In her late 20s, she was single and working as an actress when she fell pregnant. Arriving at the Royal Women’s Hospital in 1941, she was told three times by the social worker tried to relinquish her child, to “think of the baby”.

‘‘They could see I was determined to keep my baby,’’ Maggie recalls. ‘‘I was older and stronger than other young and vulnerable girls they dealt with.’’

Afforded no support or advice about parenting welfare, Maggie took her baby boy home.

‘‘I tried valiantly for some thirteen months, including breast-feeding him for five months while working in the theatre.”

Eventually the stress became too much to bear, and she and her baby boy moved into her parent’s house, however the home environment grew volatile and sometimes violent.

‘‘I had no money and no work,’’ says Maggie. ‘‘I was living in a dangerous environment. I agonised for weeks, but all the time this situation was affecting my child.

‘‘I had come to the end of the road.’’

After putting her child up for adoption, Maggie recalls isolating herself, grieving and sobbing for ten days.

‘‘Doing that saved my sanity; most mothers were not permitted to grieve; they were told … ‘forget about it, put it behind you and get on with your life’.’’

Jo Fraser, secretary of the Australian Association for Relinquishing Mothers, says the prospect of a symbolic apology underscores the importance of the senate inquiry.

“We want an apology from the federal government, and we’d like funding put in place for counselling for everybody — not just relinquishing mothers and fathers, but also children.’’

The senate report has been handed to the Attorney-General’s department, which will provide its response to the findings by May.

* Association of Relinquishing Mothers (ARMS Vic): 9769 0232, for support groups.

* VANISH Inc: Phone: (03) 9328 8611, Toll Free: 1300 VANISH (1300 826 474)