THREE days before the US presidential election it was clear Big Bird had swung it for Barack Obama.

Republican nominee Mitt Romney’s threats to cut funds to the national Public Broadcasting Service might never have caused such a backlash if he hadn’t mentioned the ginormous yellow canary of Sesame Street fame.

“I like PBS. I love Big Bird . . . but I am not going to keep spending money on things we have to borrow money from China to pay for,” Romney declared.

People took to the streets of Washington DC en masse for the most unlikely demonstration of our times.

“El-mo! We won’t go! What do we want? Cookies! When do we want them? Now!” they chanted.

Such is the power of puppets.

They can not only scupper would-be presidents, but also enchant royalty and reduce grown men to tears, as Steven Scott and Sue Blakey well know.

Scott is a professional puppet-builder and one half of the Woodend-based company The Festive Factory.

Together he and Blakey, a trained mime artist and puppeteer, can count Queen Elizabeth and the royal family of Qatar among their audiences in more than two decades of entertaining.

“Puppetry, for me, is the quickest way to tap into the child within everybody,” Scott says.

“We’ve all seen the big tattooed bloke with the blue singlet on, walking through the fair like it’s the last place he wants to be. He’s there because ‘I have a missus and kids, so here I am’. Nothing amuses him until a puppet dog cocks its leg on the side of him.

“With one small puppet you can reduce a big brute down to a gurgling little baby in no time at all, and to me that’s magical.”

“It’s not just about novelty,” adds Blakey, who mainly performs inside full-body puppets.

“Novelty wears off very quickly. It’s about engaging people at a level that their soul connects with.

“A puppet gives you licence to approach absolutely anybody and everybody, any culture, any head space, any level of disability if you read them and they say it’s OK to approach.”

Throughout history and across cultures, puppets have provided a dramatic metaphor to both perpetuate and parody the prevailing mores.

Being entirely unconcerned about who is pulling the strings, puppets have been used with equal success to spread conservative church doctrine and promote contraceptive messages. They’ve been employed as communist and Nazi weapons of propaganda and as a means of protest during the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia and later during the Vietnam war.

The Festive Factory plans on putting puppets to yet another use, promoting philanthropy in primary schools.

“We work with children to create two puppets: one to keep, one to send to a child in need in places like Lesotho in Africa,” Steven Scott explains.

“We teach them the basics of working with latex and spend two hours over four days with them.

“It’s not just about making the puppets; it’s about building empathy for children who don’t go home to PlayStations.”

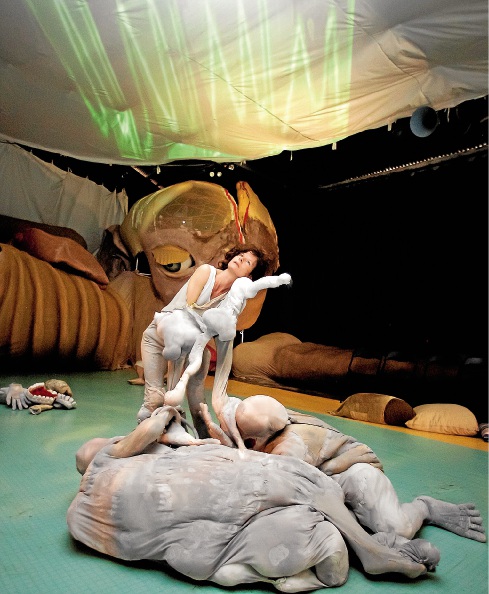

It can be difficult to tell whether the Snuff Puppets are a force of good or evil, but for every person the landmark Footscray-based company has affronted, disgusted or just plain alarmed, many more have got the message and gone forth. Everybody — the most recent Snuff production — featured a giant 22-metre puppet body complete with a giant bottom that excreted performers as faeces and included a warning to the audience they might be eaten by an over-sized mouth.

The company’s founder and artistic director, Andy Freer, explains that the Snuff is about shining a light on society’s gnarly bits and provoking thought.

“Culturally, in the First World, there are lots of issues around sexuality, morality and what’s taboo.

“I suppose because it’s a secular society we can talk about it, but we still all end up giggling behind our hands anyway.”

Freer understood the power of puppetry early on, having been “blown away” as a child in the ’70s by a performance of Teatra de la Claca featuring puppets designed by the great surrealist Joan Miro in a story based on the Spanish Civil War.

The magic of puppets, particularly of the giant kind where the audience can’t see the human performer or how a creation is operated, is in that suspension of disbelief.

“People really believe it’s real, yet they know it’s not,” Freer says. “It’s a funny thing, especially with adults – they sort of lose their sense of reality for that moment.

“It’s quite a funny way to tap into people where they sort of lose themselves. That’s exciting and fun, a theatrical moment in itself.”

People find themselves through puppetry, too. After Everybody, Freer headed for India and others in the company made for Thailand as part of Snuff’s extraordinary People’s Puppet Project.

It’s a program designed to promote the telling and keeping alive of the stories, fantasies and myths of other cultures in face of the white bread and Coca Cola of global homogenisation.

It’s culturally sensitive, Snuff.

But don’t get too comfortable, boys and girls; the company’s not going all politically correct and cutesy despite Freer’s claim he wants “Snuff Puppets to be the Muppets of Australia”.

I fall straight into the trap. “You’re really thinking of a movie?”

That’s right, says Freer.

A Snuff movie.