PRECEDE: serrated tussock is a drought-tolerant weed of national significance, and as reported by Star Weekly, the Victorian drought is exacerbating the issue of its spread in some areas including Moorabool – adding to the challenges faced by local landholders and farmers. Oscar Parry spoke with members of the Victorian Serrated Tussock Working Party (VSTWP) about the wide-reaching impacts of the weed.

A mass of slender, grassy leaves with flowerheads that produce a purple colour towards late spring – serrated tussock might sound appealing, but the many challenges it poses to local landholders, its damage to native grasslands, and its bushfire risks are devastating.

In areas of high concentration, including Moorabool and surrounds, many landowners and farmers are dealing with high numbers of the weed as its stronghold increases due to recent drought conditions.

Listed as a weed of national significance, this highly invasive plant covers more than a million hectares across New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and the ACT.

According to the Victorian Serrated Tussock Working Party (VSTWP) – a community-managed organisation that aims to reduce the harm of the weed – serrated tussock has been described as causing a greater reduction of pasture and grazing carrying capacity than any other weed in Australia and is estimated to have cost more than $40 million per year in control and lost production – with $5 million per year spent for its control in Victoria alone.

The organisation states that the biodiversity of native grasslands are threatened by its spread, concentrations of the weed can be a significant risk in bushfires due to the flammable nature of the plant and its seedheads, and on farms, it can drastically affect pastures for livestock and cause death if eaten, attach itself to machinery and vehicles, and require large amounts of time and money to address.

Native to countries in South America – including Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, and Peru – it is thought to have first been introduced to Australia in the early 1900s.

According to the VSTWP, a patch of about 10 acres was first recorded in Victoria in 1954 in Broadmeadows.

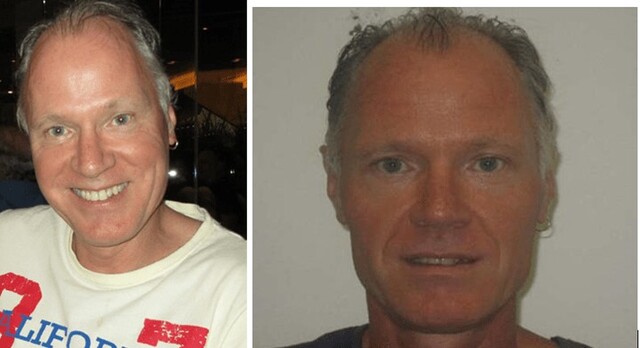

VSTWP extension officer Ivan Carter has conducted extension projects in Clarkefield, Riddells Creek, Sunbury, Gisborne and Bullengarook and provided one-to-one extension to over 1000 land owners for serrated tussock infestations.

He said the core area of infestation of serrated tussocks in Victoria includes the area between Bacchus Marsh and Geelong, Melton, and most of Moorabool.

“That’s close to where the first serrated tussock was found in Victoria, which was in Rowsley Valley … just over the back of Maddingley – and the reason for that is that it prefers a slightly drier climate where there’s less competition in the grasslands or the pastures,” Mr Carter said.

“Once you get out further west and north of Moorabool – closer towards Ballarat – it actually doesn’t compete well with good ground cover … further towards Ballan even … the most dense areas are definitely around Wyndham Vale, Bacchus Marsh, Rockbank, and Werribee.”

Mr Carter said there can be storms of airborne serrated tussock seeds, created when the weed numbers build up, they dry out, and a hot wind – usually around mid to late spring – causes all of the seeds to fly off and rain down on other areas.

“I would be predicting one [this year] for sure – it’s just been a super dry 12 months, and it … means that a lot of farmers have gone into winter without much cover because there wasn’t rain early enough, so the pastures are a bit behind what people would normally prefer – so, of course, what pops up first? The weeds,” he said.

As the weeds can harbour up to 100,000 seeds per year, Mr Carter said local governments have begun to encourage landowners to de-seed their plants when they cannot control numbers.

He said that as the seeds can spread through the wind, and then remain in soil for seven years, landowners can be affected by the properties around them – even if they are effectively managing serrated tussock on their own properties.

“There’s just so many priorities for landowners and primary producers that they have to deal with, and I think for some people, serrated tussock can be the straw that breaks the camels back – particularly when their neighbours aren’t managing their tussock,” Mr Carter said.

“That’s when we see people on the verge of just giving up – because they don’t have any community support around them.

“That’s the most common question we have … how to identify it … the second most common thing is ‘what do I do about my neighbours that aren’t doing anything?’”

Mr Carter said he feels the main challenge with dealing with serrated tussock is that it’s not identified early enough most of the time, where it builds up in numbers – and by that stage, it usually becomes expensive and time consuming to manage.

In an example of its financial impacts, he said a landowner in the Rowsley Valley at one stage had a pile of receipts that totalled over $200,000 in just treatments alone.

“That was just in buying herbicide and controlling tussock, not even the time it took, but just the financial costs,” he said.

Mr Carter said the VSTWP can help landowners to identify serrated tussock, encouraging those who are unsure to contact the organisation

“Once you know what it is, you’ve sort of taken the first step to doing something about it,” he said.

Pentland Hills Landcare Group and VSTWP community representative Joe Lesko said the damage caused by invasive weeds like serrated tussock can have wide-reaching effects on landowners.

“Personally, we’ve had our farm for 40 years, and … it becomes, basically, a part of you,” Mr Lesko said.

“Maintaining and having it well managed is like an extended indicator of your own health, physically and mentally, so it’s important to your health that you can manage and be on top of it.

“If our neighbours in close proximity aren’t doing the same, we face continued re-emergence of the seed … flying in from other people’s properties. That’s why … a total approach is the only thing that can ever [succeed].”

Mr Lesko said under a community of practice model, landowners and all government departments play a role in combatting the weed.

“For start, compliance is actually like a fallback position basically under the community of practice model – landowners are encouraged to fulfil their responsibility willingly, but for various reasons, there’s almost a certain percentage of people who … do nothing even though they are responsible for control of … tussocks on their land,” Mr Lesko said.

“Non-compliance to the land act threatens the good work done by all those who have fulfilled their responsibilities … so compliance basically is … the last resort to getting action.

“We can only encourage people to take it seriously and get the work done – so it’s basically up to the state government who [has] the major compliance … responsibilities … in some areas they do follow it too, but other areas they don’t.”

Mr Lesko said he would like to see more government recognition of the importance of managing the issue, and more of a budget allocated to it.

“It means federal, state government, and local government. The three levels of government can have roles to play if they all work it out,” he said.

“Bacchus Marsh 30 or 40 years ago had three or four officers whose role was to go out and encourage people … and those positions don’t exist any more in Bacchus Marsh.”

He said he believes Landcare is a key element for success, and the VSTWP hopes to link and combine with the Landcare movement to continue addressing the issue under the community of practice model.

Melton director of city futures Sam Romaszko said the council takes biosecurity and the management of invasive weeds seriously and is committed to sustainable environmental practices across the municipality.

“We proactively engage with the [state government], who is responsible for enforcement, and we also provide support to landowners to assist with managing serrated tussock,” Ms Romaszko said.

The state government was contacted for comment.