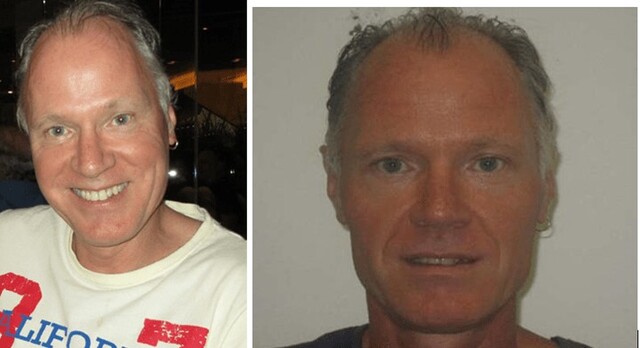

For thirty years, a normal weekend for Wendy Cavanagh involved going to the footy, and out to lunch with her husband and their friends. They’d worked their entire lives and had no issues providing for their four children.

These days though, Ms Cavanagh said a pub lunch would chew through about half of her weekly living allowance.

Ms Cavanagh is 82 and her husband, Graham, 76. They are now retired, but rising living costs are stretching their pension paper-thin.

They moved into an independent living retirement village in Melton after their old rental became too expensive, but rent still takes up over half their income, and essentials like electricity and groceries are taking up more of what’s left over.

Ms Cavanagh said she has to be “very methodical” about how she shops.

“One week I’ll do cleaning products and the other I’ll do food. I can’t afford to buy big cuts of meat, I barely eat meat because we really can’t afford it,” she said.

In September this year a social worker recommended the Combined Churches Caring Melton’s food bank service to Ms Cavanagh.

Ms Cavanagh said she didn’t want to do it, that it felt embarrassing.

“It is an embarrassment because when you’ve worked all your life and you’ve been able to provide for a family and look after them and then all of a sudden now there’s just not the money there,” she said.

“It was embarrassing, but then on the other hand I’m glad that there was something there that we were able to access that made it possible for us to get through.

“We wouldn’t have gotten through that time without them, they were fabulous.”

Ms Cavanagh said she feels older people are getting the “raw end of the deal” during the current economic downturn, and Combined Caring Churches Melton chief executive Denise Morris said their story is not an isolated case.

Ms Morris said that demand for their foodbank service has increased by 58 per cent over the past 12 months, and the largest increase has been in people over 65.

She said they used to supply food for eight to 10 over 65’s a month, but in August it was more than 50.

“We’ve had a lot of people that have coped well throughout the years that are absolutely distraught that they have to reach out for help,” she said.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Consumer Price Index measures household inflation and includes statistics about price change for categories of household expenditure.

The consumer price index rose 1.8 per cent in the September quarter, and its annual increase of 7.3 per cent is the highest since 1990. Food and non alcoholic beverages alone have risen 9 per cent in 12 months.

These rises push more and more people into insecure financial situations.

Foodbank Australia’s Hunger Report 2022 stated that two million, or 21 per cent, of households in Australia have experienced severe food insecurity in the last year.

Food insecurity levels are increasing, with 55 per cent of food insecure households reporting that they can’t afford food more often this year than last year.

Foodbank Australia defines severe food insecurity as households that sometimes skip meals, or entire days of eating because there’s no money for food.

The Foodbank Hunger Report said that increasing cost of living is the most common reason for food insecurity, with 64 per cent of people citing it as a cause.

Jesuit Social Services’ Centre for Just Places executive director Susie Maloney said that older people can often be more at risk for certain indicators of disadvantage, especially chronic illness.

Chronic illness is also compounded by other factors such as public health wait times, access to quality housing, and access to quality food.

Ms Maloney said disadvantage is complex and has a lot of interconnections, her organisation, Jesuit Social Services released their Dropping Off The Edge report in 2021, which measured 37 aspect disadvantage in different postcodes across Australia.

The report indexes Statistical Area Level 2’s and gives them a rating of one to five.

Melton, Melton South, and Melton West all received the reports highest rating of one, as did many other suburbs in Melbourne’s west including Werribee East, Sunshine, Altona and Delahey.

Ms Maloney said the drivers of disadvantage in these areas exacerbate the effects of rising living costs.

“The way in which outer areas have been developed and the lack of services and the provision of services is certainly a feature of what we are seeing,” she said.

“In talking about the cost of living, clearly housing affordability, transport costs, fuel costs, are ongoing and challenging, and particularly for communities living in outer areas.

“Growth in outer areas is narrowly framed around ideas of affordability being just affordability of a home, all the other living costs are now becoming much more significant, and so we have to really change the way we think about what affordability means.”

Ms Maloney said that the recent federal budget contained some positive signs around the increase in supply of social and affordable housing, but there’s more that needs to be done.

She said it’s especially disappointing that there’s no commitment to increase the Jobseeker payment and other income support.

Hawke MP Sam Ray said he’s been fighting for the best outcomes for communities in his constituency.

“The cost-of-living package will ease the cost of living pressure on households in Melton, Bacchus Marsh and Ballan by providing almost 7,000 local families with access to cheaper childcare, increasing paid parental leave to six months and slashing the cost of medicines at the pharmacy by $12.50 per script,” he said.

For Ms Cavanagh, the only option at the moment is to grit her teeth and keep going.

“I’d like to be able to just walk into the supermarket and be able to buy a decent piece of steak, but all we can buy is a packet of sausages and then I’ve got to divide them in two, so it lasts for two meals. It’s very frustrating. It’s very depressing,” she said.

“You don’t know what’s going on in other people’s lives, you can’t just look at someone and judge them

“It’s brought about by the economy really. We haven’t told many people, we haven’t even told the family, but we wouldn’t have got through without [the foodbank]. It is what it is.”